Roughly translated as "Unification by Military Rule", it's usually assumed that Nobunaga considered war and aggression as a political statement, a bit like the Roman Empire, that based on war and territorial annexion his purpose and sustenance.

This is, under obvious aspects, true, but it's simplicistic and kinda idiotic to limit the acumen of Nobunaga's government over war alone.

Truth is, if we pay a little more attention to what Nobunaga's social and urbanistic improvement meant, we could find where the modernity of Nobunaga's mindset really was: the use of politics as a weapon.

He instituted it on 1568 for the first time in Kano and Azuchi, and it spread to the Kinai province** instantly.

Originally, the commercial activities of a town were administred by certain "centers of power" who decided on fees and regulation for the distribution of goods: those were the noblesmen and the temples, who forced merchants and artisans to pay certain fees to them to access the markets to sell their goods to the people. During the Sengoku era, with the dissolution of the political power of the Japanese nobility, these special benefits were hold by local daimyo.

So, when Nobunaga declared his provinces as a place where merchants could freely access to sell their goods without paying for permission, implemeting the communication and travel by removing further toll gates in his lands, he wasn't just promoting jokamachi, the prosperity of the town around his castle, but was attacking those who gained money from the previous enstablishment: local daimyo and most importantly, the jinai, the temple precints, that pretty much worked as "independent provincial towns possessing extraterritorial rights", the pulsing heart of the Ikko Ikki.

In one smooth operation he gained prosperous provinces and weakened the "financial position" of his opponents.

Many scholars state that they were just directed to a proper administration of the lands and an adequate tax system, but I personally embrace the analysis of Matsuo Yoshitaka, reported by Lamers on his essay, where the sashidashi is mostly recognized as a tool to "levy military duties".

It's noted how these surveys were mostly dedicated to local military proprietors rather than temple landowners, and how the taxes were converted to rice, an "uniform currency" of the time.

Basically, given the production of rice, it was easy to determine the "wealth" of a local proprietor and how he could contribute to a military campaign. What followed the surveys, in fact, was a series of regulations to calculate the supply of military duties in accordance to the income.

Whenever Nobunaga placed "special governors" in those areas, or appointed a new governor in a newly acquired province, his reccomendations were along the lines of "Don't be greedy: determine what is due, ascertain what is paid"-- Taxes were not just a mean to gain wealth and live comfortably, they were a source to make provisions for harder times.

This is not something that Nobunaga "invented" or that we can learn something from, but it's indeed a peculiar, functional and modern character of his government that is definitely Worth to spend a few words on.

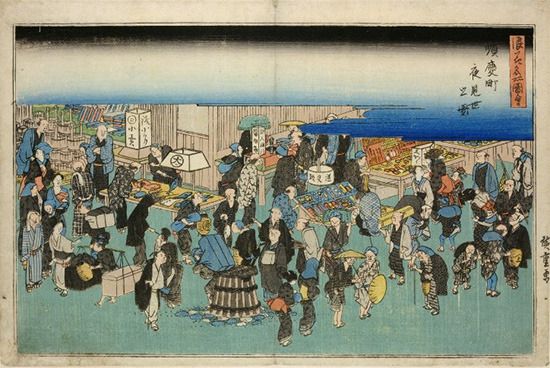

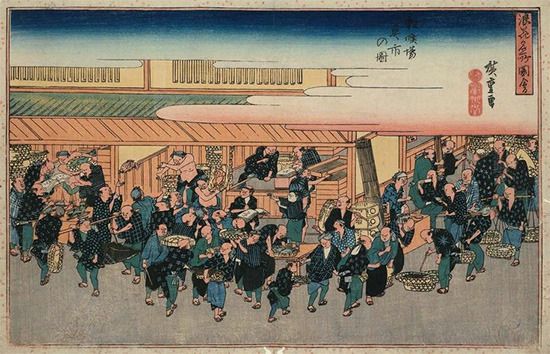

Even if the prints are dated 1834, so they can't depict how markerts looked during the Sengoku Era, they give a good appeal of one of the areas most involved in the reforms of Nobunaga.

For this reason I focused my selection on depictions of famous market of the city. The first print is dedicated to the "night market" of Junkei-machi; the second is the "rice market" of Dojima; the last is dedicated to the "fish market" of Zakoba.

If you want to see bigger renditions of the whole collection, you can check this website.

For the compilation of this article I checked the following references:

J. Lamers "Japonius Tyrannus"

G. Elison, B.L. Smith "Warlords Artists and Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century" (partially consultable on GoogleBooks)

M. Colcutt, "Japan's Medieval Age: The Kamakura & Muromachi Periods"

*This "market" stays for "privately controlled market". Don't think of them as our modern "street markets", which resembled those of Nobunaga.

** Must be noted that Nobunaga didn't apply the rakuichi rakuza in Kyoto and Nara, where the local guilds were protected by his government.

No comments:

Post a Comment