I love presenting peculiar ukiyo-e and talk about them, so, as I did on my personal blog when talking about the Honnoji Accident, I decided to repeat the experience, this time focusing on a curious legend about Nobunaga.

I'll report today's story as coming as straight from Wikipedia, but various versions exist: "The cycad tree in the temple is over 1100 years old and is well known for its mysterious history. Oda Nobunaga [...] transplanted this cycad to Azuchi Castle in what is now Shiga prefecture. However, every night a strange voice was heard in Azuchi Castle saying “Take me back to Myokokuji”, and an unnatural atmosphere covered the castle and disturbed the people there. This angered Nobunaga and he let his men cut the tree down. The tree is said to have bled from the blows, fainted from the pain and looked so much like a great snake that even brave Nobunaga became afraid and sent the tree back to Myokokuji. "

This is an example of a typical yokai story relished with a famous samurai and a "monument" (in this case a "natural" one), more than enough to make it a nice subject for woodblock prints.

I'll start this "digest" with the first specimen in chronological order that I got to find: a print by Yoshifusa, dated 1860.

This print features a furious Nobunaga rushing to inspect the noisy cycad with Ranmaru, who's helding a lanter that enlightens only a little bit of the tree, inscreasing the "scary factor", since the most of the tree is left in mysterious darkness.

Nobunaga is grabbing his sword, maybe ready to strike a first blow against the moaning sotetsu.

This second print is dated 1864 and it's a work by Yoshitsuya.

This print is part of a collection dedicated to the battles of Hideyoshi.

Curiously it depicts the legend of Nobunaga and the cycad instead of an actual battle.

Here the yokai vibe of the cycad is shown in all its terrifying glory: the tree is shown as Nobunaga's men are trying to cut it down; at this point it shows monstruos features, snake tongues and demonic eyes, as it pours drops of blood (here rendered with the violence and dynamism of bullets) on the men that can only run away in fear as Nobunaga can't hide his disappointment and Ranmaru his surprise.

It's interesting to note the snow covering the branches of the cycad, suggesting the full winter season.

After the dynamism of Yoshitsuna, it's time for stepping back to another elegant rendition of the story, this time rendered by Yoshitoshi in a print of 1865:

We have again the partial illumination of the tree by Ranmaru, and Nobunaga pointing treatingly against the tree, that appears as moving in the darkness.

As I told you before, in fact, there are various versions of this story.

In the one picked by Yoshitoshi, Nobunaga asked Ranmaru to cut the tree down once he decided that he had enough of the cycad's crying, but before he could do so the cycad ran away from Azuchi to reach its original location.

Yoshitoshi interpreted this legend from his collection of pictures dedicated to ghost stories again in 1891, with a "remake" of the same collection:

This time the protagonist of the picture is Ranmaru alone, startled as he witnesses the run of the cycad into the darkness.

This artwork is extremely refined and the elegance of the composition stuns the watcher.

--So, if you ever happen around Osaka make sure to take a peek to the karesansui garden and its marvellous millenary cycad (now recognized a national natural monument in Japan) hosted in the grounds of Myokokuji! It would be a way to pay your homage to this whiny yet undefeated "enemy" of Nobunaga!

Tuesday, 29 April 2014

Monday, 28 April 2014

Nobunaga and Religion: a few considerations

When the issue of religion is contemplated in Nobunaga's life, people tend to dismiss the whole thing claiming that he was an atheist, or, even better, they quote the whole deal with the self-deification at Azuchi, turning him into a heretical megalomaniac.

The words of Luis Frois on the issues and Nobunaga's constant (and brutal) persecution of Buddhist confederates are usually reported ss evidences of such a theory.

In a correspondence with a fellow missionary dated 1569, Frois wrote that "he openly declares that there is no creator of the universe, no immortality of the soul, no life after death", speaking about Nobunaga's beliefs, portraying him as a lost cause for what concerned Catholicism.

The reports of Frois sure gave us an impression, but we must not forget that Nobunaga was not a Westerner, so trying to define his spiritual disposition from a Catholic point of view may be quite tricky.

Of course I'm not stating that Nobunaga was as a fervently religious person as Uesugi Kenshin or Takeda Shingen were (both of them received monastic education), but that we can't really describe him as an "atheist" (or even as a "satanist", as popular culture taught us) according to our modern standard, despite his verified pragmatism and unorthodox solutions when it came to del with the Ikko Ikki & Co.

First of all, we don't have to identify the concept "religion" as a mere matter of "believing in supernatural entities".

Religion is, firstly and foremost, a "cultural matter".

Giving a trascendental or mystic outline to the identity of a community is the first step of human civilization, it's how people recognize themself as part of a "society".

The "rules" according to which this society develops derive from some kind of "mythology" that legitimizes its identity, and sometimes superiority, among "others".

It's the same for every monotheistic religion, but this basical anthropologioc principle applies to ancient Greeks, Egyptians and of course even to Shintoism, the indigeous religion of Japan.

During Nobunaga's time, the religious compartment was shared between Shintoism and Buddhism.

As Shintoism was the religion more popular with the low classes and rural society, because of its emphasis on family, ancestors and farming, Buddhism was the religion of the warrior class; it was common to have the kids of a samurai to study in a Buddhist temple so to apprehend what the warlord of the time considered as "ethic": value the loyalty to superiors, need for decorum and feelings of superiority for those who didn't belong to the samurai class.

Even Nobunaga received such an education. It's said that he studied in a temple by Kiyosu castle, and the influence of Takugen Shuon, a bonze of the Rinzai sect, over Nobunaga and the Oda family is well-known and documented.

It's him who suggested the name "Nobunaga" for the boy's genpuku to Nobuhide, Nobunaga's motto "Tenka Fubu" and, according to certain sources, even "Gifu" when it came to rename Inabayama castle.

Other Zen "teachers" whose friendship Nobunaga could boast were Nange Genkō, a patron of arts and fine culture, and Sakugen Shuryo, famous for his diplomatic relationships and missions in China, but they'll get later in the picture.

Sure, we don't know who took care of Nobunaga's education at the time, but we know that he spent the most of time having fun with his band of kabukimono rather than studying Confucianism, subject that he was quite acknowledged about, anyway.

The idea is that of a "country boy", a description that accompanied Nobunaga during most of his youth and even during his first clashes with powerful daimyo.

Sure his behavious do suggest a lack of higher education, but in my opinion the source of this "wildness" is to find in Shinto.

As I said previously, Shinto religion covered those sides of a Japanese daily life that dealt with with traditional, "regional" issues.

Praying for protection against famine, illness and the like was supposed to be a Shinto duty because of the "local character" of such issues.

Nobunaga had a strict connection with Shintoism through his whole life.

In his youth he was known for being a faithful attendee of the Tennou Matsuri of Tsushima shrine (津島神社).

The festival honors Gozutennō, invoked against pestilences during summer, but it mostly focuses on celebrating the Tennō river, which course is animated by the floating of suggestive makiwara-bune, rappresenting the five villages that once formed Tsushima.

Of course I'm sure that his "devotion" here was mostly due to the appeal of the joyous festival more than genuine religious fervor, but you can say that this experience formed the conscience of Nobunaga, who saw religion as a way to give the sense of "kinship" through culture rather than politics.

Speaking of Gozutenno, it's worth mentioning the attendance of Nobunaga and his men to the Gion Matsuri in 1578.

Gion and Tsushima are connected as both festivals share the same origin of protection against pestilences, and in both festivals the support of Susanoo is invoked to keep in place a rampaging Gozutenno.

During the Gion Matsuri, Nobunaga enjoyed the view of the yamaboko parade, but also gave a splendid example of modern "public order" management, so that everyone could enjoy the festival without its rituals being interrupted or disturbed.

The other important Shinto temple strictly connected to Nobunaga's name is the Atsuta shrine (熱田神宮).

This famous shrine was originally built to host the Kusanagi sword, one of the three Imperial treasures, but it's now also the house of the Five Great Gods of Atsuta, or those deities connected with the legendary sword and the foundation of the shrine: Amaterasu, Susanoō, Yamato Takeru, Miyasuhime and Inadane.

Nobunaga came here to pray for victory on the way to the battle of Okehazama in 1560, and returned once his wish was granted to build a roofed wall hardened by mud, grease and lime, the "Nobunaga Wall" (信長塀), as a token of his gratitude.

Many legends are connected with Nobunaga's visits to Atsuta Shrine.

One refers to the Makezu no Tsuba and tries to explain the use of the eiraku coins, bringing in an exquisitely Buddhist explanation, another, more suggestive and tied to Shinto symbology, talks about two white egrets that took flight from the temple once Nobunaga and his army were done with the rituals, only to rest by the camp of Imagawa's forces, showing Nobunaga's army where the enemy was posted.

Like many other animals, egrets are considered messengers of kami, and for this reason also frequently used as an "offer" to a temple.

Even if a mere legend, the story of the egrets is a perfect example of cultural intermission on a political matter, and how a "religious" fact legitimized an historical fact.

Another Shinto shrine is mentioned when it comes to Okehazama, at least on Nagoya's touristic guides, the Hioki shrine (日置神社).

It's said that Nobunaga made a stop to pray here too, and after his victory he donated a thousand pine branches to the shrine.

It's worth noting that the deity enshrined here is Futodama, the kami to whom the Inbe clan traced its descent.

Since we mentioned the Inbe Clan we are now forced to step back and return to Nobunaga's ancestors, who claimed Tsurugi shrine(劔神社), another Shinto shrine, as their "home".

It's said that Nobunaga kept on referring to Tsurugi shrine as the shrine of his ancestors too, but unfortunately we have no mentions of a visit there, obviously because the shrine was part of enemy terrority back then.

The shrine is dedicated to Susanoo.

Browsing through the pages of the Shinchoukoki, we can find many other examples of the same kind.

They are important statements that, if Nobunaga wasn't a follower of any religion, he did understand its importance in the social structure, identity and tradition of "his people".

It's reported that in 1574 Nobunaga happened to be in Kyoto during the Kamo Matsuri at Kamo Shrine (賀茂神社).

This Shinto sanctuary complex houses one of the most important festivals of Kyoto, that in Nobunaga's times was referred as "Kamo Matsuri", but that now is famous as the "Aoi Matsuri": originally a festival to grant a bountiful harvest, it was celebrated through ritual horses races and equestrian archery.

The priests asked him if he could provide some horses for the races: Nobunaga granted them two of his favourite war horses that he personally rode in battle, and another eighteen, all of them "outfitted splendidly", so that the festival left a deep impression on the visitors.

In 1575 he happened again around the Atsuta grounds while camping there during the campaign against Takeda.

He was observing the Hakkengu (八剣宮) and noticed that it was in pitiful conditions: he promptly ordered Okabe Mataemon to take care of its reconstruction.

It wouldn't be the last time that Nobunaga cared to support and fix famous shrines of Shinto faith.

In 1579 it came to Nobunaga's attention how the wooden gutters of the Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine (石清水八幡宮) rot, ruining the whole "character" of the shrine.

He summoned his deputies of the province, and had them work on a project using bronze gutters, so that the job could last "for ages".

The work proved quite expensive and time consuming, but once it was done, a groundbreaking ceremony was held after receiving the blessing of the Emperor, and Nobunaga presented the temple a refined censer.

It's interesting to note that another wall, exactly like the one at Atsuta Shrine, was built here by Nobunaga.

In 1582, a request from Uwabe Sadanaga, one of Nobunaga's retainer, was brought to his attention by Hori Hidemasa: "the custom of rebuilding the Grand Shrines of Ise (伊勢神宮) every twenty years had been in decline for three centuries and was no longer being carried out".

I don't think that I need to tell you about the Ise Shrine. And Nobunaga either, needed to be asked twice: but this time, aware of the expenses after the deal with Hachiman Shrine, he asked Nobutada to contribute with Gifu's funds so to not "impose hardships on the populace".

I talked about Shinto, and now I'll spend a few words on Buddhism too, to close the circle.

I already mentioned his Buddhist intimate friends and "teachers" and even Frois reported that Nobunaga described himself as a follower of the Hokke sect of Buddhism, even if it's usually considered as a misunderstanding on Frois' account.

Truth is that the Buddhist temples where he usually lodged at during his trips to Kyoto belonged to the Hokke sect: I'm talking about the Myokakuji (妙覚寺) and the Honnoji (本能寺), the temple that in 1570 he claimed as his ryoshuku, or "private quarters".

It's usually assumed that Nobunaga favoured those places because the quality of the hospitality rather than the religious affiliation, but it's worth mentioning that it may be true also otherwise.

After all, the temples that Nobunaga built for his family and clan were of Buddhist affiliation: the family temple that he built at Azuchi, the Sokenji (総見寺), was a temple of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism, and an image of Kannon was enshrined there; the Sofukuji (崇福寺), the temple that he used when he moved to Gifu, belonged to the Rinzai sect of Buddhism too.

It's worth noting that also the temple that he built in 1553 to honor the memory of his former tutor Hirate Masahide, the Seijouji (政秀寺), was of Rinzai affiliation, while the Banshoji (萬松寺), the family temple built by Nobuhide in 1540, was of Soto sect.

After Nobunaga's death, many temples were dedicated to his memory.

The Sokenji (総見寺) in Nagoya was originally built in Kiyosu, and was dedicated to his father and brother's memory by Nobukatsu after their death at Honnoji. Like its homonimous in Azuchi, the temple belongs to the Rinzai sect of Buddhism.

In 1587, Hideyoshi dedicated the Daiun-in (大雲院) to the memory of Nobutada and Nobunaga: "Daiunin" is the posthumous Buddhist name of Nobutada.

Another Buddhist temple that hosts a memorial of Nobunaga is the Amidaji (阿弥陀寺), a temple of the Jodo Sect in Kyoto: it's said that the monk Seigyoku, who had deep connections to the Oda family, gathered the remains of Nobunaga, Nobutada and the other men who met their death at Honnoji and buried them in the temple grounds: the ashes have been equally divided through the temples of Amidaji, Honnoji and Kenkun Shrine (建勲神社), which is the most recent temple dedicated to Nobunaga: this Shinto shrine was built in 1870 by one of Nobunaga's descendant, Oda Nobutoshi, with the blessing of Emperor Meiji, and Nobunaga himself is enshrined here.

Long story short, Nobunaga wasn't an iconoclast, an atheist or a rebel like many likes to think to justify this or that "cruelty".

He never denied the importance of religion or vilified its contents: whenever he condamned or executed a religious group or personality, it was simply because "they no longer stressed the moral practices of the nembutsu path", they "disobeyed even the ordinances of their own school" or they "were concerned only with wordly affairs".

To put it in simple words, they were acting like a political force, and not like a religious entity.

PS: Since last time I've been scolded for the lack of bibliographical references, here you go:

"Religion in Japanese History", Kitagawa, Joseph

"Feste Tradizionali in Giappone", Caillet, Laurence (trad. Dentoni, Francesco)

"Oda Nobunaga and the Buddhist institutions", McMullin, Neil Francis, which can be consulted online here.

The words of Luis Frois on the issues and Nobunaga's constant (and brutal) persecution of Buddhist confederates are usually reported ss evidences of such a theory.

In a correspondence with a fellow missionary dated 1569, Frois wrote that "he openly declares that there is no creator of the universe, no immortality of the soul, no life after death", speaking about Nobunaga's beliefs, portraying him as a lost cause for what concerned Catholicism.

The reports of Frois sure gave us an impression, but we must not forget that Nobunaga was not a Westerner, so trying to define his spiritual disposition from a Catholic point of view may be quite tricky.

Of course I'm not stating that Nobunaga was as a fervently religious person as Uesugi Kenshin or Takeda Shingen were (both of them received monastic education), but that we can't really describe him as an "atheist" (or even as a "satanist", as popular culture taught us) according to our modern standard, despite his verified pragmatism and unorthodox solutions when it came to del with the Ikko Ikki & Co.

First of all, we don't have to identify the concept "religion" as a mere matter of "believing in supernatural entities".

Religion is, firstly and foremost, a "cultural matter".

Giving a trascendental or mystic outline to the identity of a community is the first step of human civilization, it's how people recognize themself as part of a "society".

The "rules" according to which this society develops derive from some kind of "mythology" that legitimizes its identity, and sometimes superiority, among "others".

It's the same for every monotheistic religion, but this basical anthropologioc principle applies to ancient Greeks, Egyptians and of course even to Shintoism, the indigeous religion of Japan.

During Nobunaga's time, the religious compartment was shared between Shintoism and Buddhism.

As Shintoism was the religion more popular with the low classes and rural society, because of its emphasis on family, ancestors and farming, Buddhism was the religion of the warrior class; it was common to have the kids of a samurai to study in a Buddhist temple so to apprehend what the warlord of the time considered as "ethic": value the loyalty to superiors, need for decorum and feelings of superiority for those who didn't belong to the samurai class.

Even Nobunaga received such an education. It's said that he studied in a temple by Kiyosu castle, and the influence of Takugen Shuon, a bonze of the Rinzai sect, over Nobunaga and the Oda family is well-known and documented.

It's him who suggested the name "Nobunaga" for the boy's genpuku to Nobuhide, Nobunaga's motto "Tenka Fubu" and, according to certain sources, even "Gifu" when it came to rename Inabayama castle.

Other Zen "teachers" whose friendship Nobunaga could boast were Nange Genkō, a patron of arts and fine culture, and Sakugen Shuryo, famous for his diplomatic relationships and missions in China, but they'll get later in the picture.

Sure, we don't know who took care of Nobunaga's education at the time, but we know that he spent the most of time having fun with his band of kabukimono rather than studying Confucianism, subject that he was quite acknowledged about, anyway.

The idea is that of a "country boy", a description that accompanied Nobunaga during most of his youth and even during his first clashes with powerful daimyo.

Sure his behavious do suggest a lack of higher education, but in my opinion the source of this "wildness" is to find in Shinto.

As I said previously, Shinto religion covered those sides of a Japanese daily life that dealt with with traditional, "regional" issues.

Praying for protection against famine, illness and the like was supposed to be a Shinto duty because of the "local character" of such issues.

Nobunaga had a strict connection with Shintoism through his whole life.

In his youth he was known for being a faithful attendee of the Tennou Matsuri of Tsushima shrine (津島神社).

The festival honors Gozutennō, invoked against pestilences during summer, but it mostly focuses on celebrating the Tennō river, which course is animated by the floating of suggestive makiwara-bune, rappresenting the five villages that once formed Tsushima.

Of course I'm sure that his "devotion" here was mostly due to the appeal of the joyous festival more than genuine religious fervor, but you can say that this experience formed the conscience of Nobunaga, who saw religion as a way to give the sense of "kinship" through culture rather than politics.

Speaking of Gozutenno, it's worth mentioning the attendance of Nobunaga and his men to the Gion Matsuri in 1578.

Gion and Tsushima are connected as both festivals share the same origin of protection against pestilences, and in both festivals the support of Susanoo is invoked to keep in place a rampaging Gozutenno.

During the Gion Matsuri, Nobunaga enjoyed the view of the yamaboko parade, but also gave a splendid example of modern "public order" management, so that everyone could enjoy the festival without its rituals being interrupted or disturbed.

The other important Shinto temple strictly connected to Nobunaga's name is the Atsuta shrine (熱田神宮).

This famous shrine was originally built to host the Kusanagi sword, one of the three Imperial treasures, but it's now also the house of the Five Great Gods of Atsuta, or those deities connected with the legendary sword and the foundation of the shrine: Amaterasu, Susanoō, Yamato Takeru, Miyasuhime and Inadane.

Nobunaga came here to pray for victory on the way to the battle of Okehazama in 1560, and returned once his wish was granted to build a roofed wall hardened by mud, grease and lime, the "Nobunaga Wall" (信長塀), as a token of his gratitude.

Many legends are connected with Nobunaga's visits to Atsuta Shrine.

One refers to the Makezu no Tsuba and tries to explain the use of the eiraku coins, bringing in an exquisitely Buddhist explanation, another, more suggestive and tied to Shinto symbology, talks about two white egrets that took flight from the temple once Nobunaga and his army were done with the rituals, only to rest by the camp of Imagawa's forces, showing Nobunaga's army where the enemy was posted.

Like many other animals, egrets are considered messengers of kami, and for this reason also frequently used as an "offer" to a temple.

Even if a mere legend, the story of the egrets is a perfect example of cultural intermission on a political matter, and how a "religious" fact legitimized an historical fact.

Another Shinto shrine is mentioned when it comes to Okehazama, at least on Nagoya's touristic guides, the Hioki shrine (日置神社).

It's said that Nobunaga made a stop to pray here too, and after his victory he donated a thousand pine branches to the shrine.

It's worth noting that the deity enshrined here is Futodama, the kami to whom the Inbe clan traced its descent.

Since we mentioned the Inbe Clan we are now forced to step back and return to Nobunaga's ancestors, who claimed Tsurugi shrine(劔神社), another Shinto shrine, as their "home".

It's said that Nobunaga kept on referring to Tsurugi shrine as the shrine of his ancestors too, but unfortunately we have no mentions of a visit there, obviously because the shrine was part of enemy terrority back then.

The shrine is dedicated to Susanoo.

Browsing through the pages of the Shinchoukoki, we can find many other examples of the same kind.

They are important statements that, if Nobunaga wasn't a follower of any religion, he did understand its importance in the social structure, identity and tradition of "his people".

It's reported that in 1574 Nobunaga happened to be in Kyoto during the Kamo Matsuri at Kamo Shrine (賀茂神社).

This Shinto sanctuary complex houses one of the most important festivals of Kyoto, that in Nobunaga's times was referred as "Kamo Matsuri", but that now is famous as the "Aoi Matsuri": originally a festival to grant a bountiful harvest, it was celebrated through ritual horses races and equestrian archery.

The priests asked him if he could provide some horses for the races: Nobunaga granted them two of his favourite war horses that he personally rode in battle, and another eighteen, all of them "outfitted splendidly", so that the festival left a deep impression on the visitors.

In 1575 he happened again around the Atsuta grounds while camping there during the campaign against Takeda.

He was observing the Hakkengu (八剣宮) and noticed that it was in pitiful conditions: he promptly ordered Okabe Mataemon to take care of its reconstruction.

It wouldn't be the last time that Nobunaga cared to support and fix famous shrines of Shinto faith.

In 1579 it came to Nobunaga's attention how the wooden gutters of the Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine (石清水八幡宮) rot, ruining the whole "character" of the shrine.

He summoned his deputies of the province, and had them work on a project using bronze gutters, so that the job could last "for ages".

The work proved quite expensive and time consuming, but once it was done, a groundbreaking ceremony was held after receiving the blessing of the Emperor, and Nobunaga presented the temple a refined censer.

It's interesting to note that another wall, exactly like the one at Atsuta Shrine, was built here by Nobunaga.

In 1582, a request from Uwabe Sadanaga, one of Nobunaga's retainer, was brought to his attention by Hori Hidemasa: "the custom of rebuilding the Grand Shrines of Ise (伊勢神宮) every twenty years had been in decline for three centuries and was no longer being carried out".

I don't think that I need to tell you about the Ise Shrine. And Nobunaga either, needed to be asked twice: but this time, aware of the expenses after the deal with Hachiman Shrine, he asked Nobutada to contribute with Gifu's funds so to not "impose hardships on the populace".

I talked about Shinto, and now I'll spend a few words on Buddhism too, to close the circle.

I already mentioned his Buddhist intimate friends and "teachers" and even Frois reported that Nobunaga described himself as a follower of the Hokke sect of Buddhism, even if it's usually considered as a misunderstanding on Frois' account.

Truth is that the Buddhist temples where he usually lodged at during his trips to Kyoto belonged to the Hokke sect: I'm talking about the Myokakuji (妙覚寺) and the Honnoji (本能寺), the temple that in 1570 he claimed as his ryoshuku, or "private quarters".

It's usually assumed that Nobunaga favoured those places because the quality of the hospitality rather than the religious affiliation, but it's worth mentioning that it may be true also otherwise.

After all, the temples that Nobunaga built for his family and clan were of Buddhist affiliation: the family temple that he built at Azuchi, the Sokenji (総見寺), was a temple of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism, and an image of Kannon was enshrined there; the Sofukuji (崇福寺), the temple that he used when he moved to Gifu, belonged to the Rinzai sect of Buddhism too.

It's worth noting that also the temple that he built in 1553 to honor the memory of his former tutor Hirate Masahide, the Seijouji (政秀寺), was of Rinzai affiliation, while the Banshoji (萬松寺), the family temple built by Nobuhide in 1540, was of Soto sect.

After Nobunaga's death, many temples were dedicated to his memory.

The Sokenji (総見寺) in Nagoya was originally built in Kiyosu, and was dedicated to his father and brother's memory by Nobukatsu after their death at Honnoji. Like its homonimous in Azuchi, the temple belongs to the Rinzai sect of Buddhism.

In 1587, Hideyoshi dedicated the Daiun-in (大雲院) to the memory of Nobutada and Nobunaga: "Daiunin" is the posthumous Buddhist name of Nobutada.

Another Buddhist temple that hosts a memorial of Nobunaga is the Amidaji (阿弥陀寺), a temple of the Jodo Sect in Kyoto: it's said that the monk Seigyoku, who had deep connections to the Oda family, gathered the remains of Nobunaga, Nobutada and the other men who met their death at Honnoji and buried them in the temple grounds: the ashes have been equally divided through the temples of Amidaji, Honnoji and Kenkun Shrine (建勲神社), which is the most recent temple dedicated to Nobunaga: this Shinto shrine was built in 1870 by one of Nobunaga's descendant, Oda Nobutoshi, with the blessing of Emperor Meiji, and Nobunaga himself is enshrined here.

Long story short, Nobunaga wasn't an iconoclast, an atheist or a rebel like many likes to think to justify this or that "cruelty".

He never denied the importance of religion or vilified its contents: whenever he condamned or executed a religious group or personality, it was simply because "they no longer stressed the moral practices of the nembutsu path", they "disobeyed even the ordinances of their own school" or they "were concerned only with wordly affairs".

To put it in simple words, they were acting like a political force, and not like a religious entity.

PS: Since last time I've been scolded for the lack of bibliographical references, here you go:

"Religion in Japanese History", Kitagawa, Joseph

"Feste Tradizionali in Giappone", Caillet, Laurence (trad. Dentoni, Francesco)

"Oda Nobunaga and the Buddhist institutions", McMullin, Neil Francis, which can be consulted online here.

Saturday, 26 April 2014

References for 花の香は撞く (Hana no Ka wa tsugu) - Pt.I

You should know about my amateurish experience as a comic maker, I'm a girl full of inspiration but sure squeezing all those suggestions into a proper plot is difficult, expecially when you start to find all kind of infos and you realize that you're just going to use a mere 3% of them anyway.

In an attempt to clarify my vision of the story I decided to write and share this series of posts related to Nobunaga's family, expecially his sons, daughters and nephews, since there's so little information about them.

I don't think that all these characters are going to star in my next Nobunaga's manga project, Hana no Ka wa tsugu ("HanaKa" for short), but once I started I couldn't stop and I had to indagate further. Unfortunately I could access only a little bit of material and apparently there are many parts left out in official storiography anyway.

So, keep in mind that the posts going under the "projects" tags do have a historical foundation, but I also took the liberty of adding personal interpretations and speculations according to my narrative needs (but don't worry, I'll make sure to separate the "historical" from the "fictional" information clearly enough)-- Obviously if you know other historical bits that you want to share and could help with broadening the biographies of these characters feel free to comment and share!

Well, after this boring introduction, let's go to the actual contents!

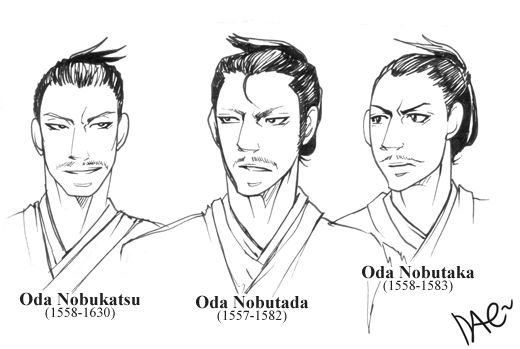

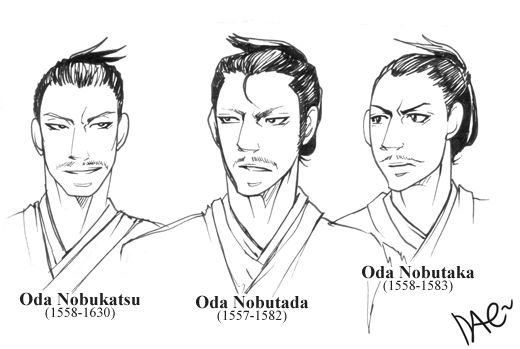

This first post will focus on Nobunaga's sons, or at least the first three of them.

ODA Nobutada (1557-1582)

ODA Nobutada (1557-1582)

Of course we'll start with Nobunaga's firstborn and heir, Nobutada.

He was born in 1557 in Owari province at the Ikoma mansion, his mother being one of Nobunaga's (favourite) concubine, Kitsuno (吉乃, sometimes also spelled as "Yoshino").

His childhood name was Kimyoumaru (奇妙丸), with "奇妙" meaning "strange", "bizarre"-- It's said that the first time that Nobunaga saw his child's face commented on it saying the he had "a strange face", so he picked such a name for him.

In 1567, following the attempt to form an alliance between the Oda and the Takeda, Nobutada received Matsuhime (松姫), Takeda's daughter, as his wife. The girl kept staying at the Takeda household because of her young age, though, where she'd be treated as "the entrusted lawful wife of Nobutada".

In 1572 he had his genpuku ceremony, where he got the name Oda Kankuro Nobushige (勘九郎信重), that became Nobutada later on.

Right after the genpuku, he had his uijin, his first military campaign, when Nobunaga agreed to bring him to the Kohoku campain against the Azai.

On the same year, Takeda Shingen attacked the Totomi province, causing the reaction of Ieyasu Tokugawa and consequently of his ally, Nobunaga; the marriage between Nobutada and Matsu was broken.

After his first battle, Nobutada kept on fighting almost continuosly, assisting his father: he took part to the campaigns against Honganji (1573), Nagashima (1574) and Nagashino (1575).

In 1575 he led the attack against Iwakura castle, taking it after executing all its inhabitants.

In 1576 he was entrusted Gifu Castle together with the family headship and Owari and Mino provinces.

From there on was another series of battles and showers of titles and honors from the Imperial family and his father, 'til the definitive defeat of Takeda Katsuyori and the extermination of his whole family.

In 1582 when at age 25 he could boast an outstanding career.

It's curious to note that after the "Matsuhime incident" he didn't marry again.

Weird, since back in the time to have a family and grant discendants to the clan was of the uttermost importance.

He did fathered two children, though: Hidenobu, born on 1580 (his mother was a concubine, probably a daughter of Shiokawa Nagamitsu, a certain Suzu [寿々]) and Hidenori, born on 1581 (no informations on his mother are available).

--There's a theory according which Nobutada and Matsuhime kept a letter correspondence and the two never stopped loving each other: proof (?) is that Matsuhime became a nun only after Nobutada's death, and that she went by the nun name 信松尼, using the "松" of her proper name and the 信 from "Nobutada"... But as suggestive as the story is, an actual historical source is not provided (I mean, also her father's name started by "信")...

From this short account on his life you can tell that Nobutada could sport an ambitious and aggressive personality: his direct attacks and calculating cruelty made him the quintessence of a Sengoku warrior, and he also shared the tastes of his father when it came to entertainment.

There are mentions of various precious presents from Nobunaga, and reciprocal tea cerimonies hosted after the built of Azuchi castle (1577/78).

He enjoyed sumo matches with his brother Nobukatsu in Azuchi (1578/80) and his father's calvacades and sagitcho festivals through Kyoto (1581/82); he was a fan of horse riding: in 1581 he ordered men of Owari and Mino to build a riding ground by the the riverbed of Nagarakawa, where he used to ride everyday.

But it wasn't just because of similar hobbies or mere war prowess that Nobunaga favoured Nobutada: he was also assigned managing tasks which perfect execution proved his reliability.

He took care of the work on Azuchi's castle during Nobunaga's trip to Kyoto (1576), he was assigned to found the reconstruction of the Ise shrine (1582) and he managed to reconstruct the destroyed residence of Shingen in Kofu, turning it into a majestic temporary palace where Nobunaga set his quarters (1582).

Keeping this image in mind, it was no surprise that in in 1582 Nobunaga was planning to give the administration of the state affairs to his capable son.

When people think of Nobutada, they like to imagine a perfect fine man, a sort of Nobunaga but with an amiable personality.

In my opinion Nobutada shared the same exact personality of Nobunaga, but probably without any of his rage fits, since we can't find any mention of them, thus probably the image of a "reasonable" person.

By scrolling his deeds I can't help but imagine Nobutada as a son eager to please his father, but also to prove himself better than him: he was aware that being an "equal" to Nobunaga was not enough, so here's his omnipresence on the battlefield, his rushed attacks, his bravery and his cruelty: he never hesitated to cut heads to present to his father, the most precious being those of Katsuyori and his son Nobukatsu (this sure was a popular name back then, uh XD ?) or to exterminate the clans who proved disobedient.

Lamers mentions that Nobunaga wanted to cut the head of Katsuyori himself, so when Nobutada proceeded to do it himself, he was probably uncaring of his father's wish, yet completely devoted to his cause, aware that he was about to inherit his legacy.

ODA Nobukatsu (1558-1630)

Nobukatsu was Nobunaga's second son.

He was born in 1558 at Ikoma mansion, and again his mother is supposed to be Kitsuno, also if this theory is being contested recently, as in Nobutada's case.

His childhood name was Ochasenmaru (茶筅丸).

In 1569 Nobunaga decided to attack the Ise province, where he clashed against the Kitabatake clan, led by Tomonori and his son Tomofusa.

The one against Okawachi castle was a pretty massive siege, that Nobunaga won by reducing his opponents to starvation: Tomonori surrendered and offered the headship of his family together with their home castle to Ochasen as long as their lives were spared. Nobunaga agreed and put a young Nobukatsu into Okawachi castle with Tsuda Kazuyasu as his protector.

He then divided the other vital spots of the province through Takigawa Kazumasu and his younger brother Nobukane, who gained the castle of Ise-Ueno, thus pacificating Ise.

To enforce his position, Ochasen was married to Yukihime (雪姫), a daughter of Kitabatake Tomonori.

In 1572 Ochasen had his genpuku, where he got his name of Kitabatake Tomotoyo. He got the name Nobuoki after he became the head of the Kitabatake clan, in 1575.

In 1576 he proceeded to assassinate his father-in-law, apparently under Nobunaga's orders, thus turning into the absolute governor of the large province of Southern Ise.

Nobukatsu is famous for his "botch" at Iga invasion in 1579, but truth is that his military prowess was no less than Nobutada's, despite the little chances that he had to shine, due to unfavorable position rather than poor skills in battle, in my opinion.

We have no mention of Nobukatsu's uijin, but the first battle that he took part in was the Delta Campaign against Nagashima's Ikko Ikki in 1574. He led one of the large ships the composed the joined operations of the naval units: he was escorted and supported by his troop commanders and was part of that "sight as dazzling as a multitude of shining stars seen among swirling clouds", as reported by Ota in his Shinchoukoki.

In 1575 he took part in the Echizen Campaign, part of that "army of thirty thousand" which units "competed with every other".

We have to wait for 1577 to see Nobukatsu back in action: together with his brothers, the joint armies of Owari, Mino, Omi and Ise assembled in Kii Province to face the Saika's Ikko Ikki. Their "echelon" was sent to follow Mitsuhide's detachment on the main road, which was "full of obstacles".

In 1578 Nobukatsu appeared again on the Osaka front, together with other famed generals, under the lead of Nobutada, which was designed by Nobunaga as the commander-in-chief of the campaign, being the de-facto head of the Oda Clan since 1576.

He took part in a reconnaissance mission in Harima on the same year, followed by the siege of Kanki to face the Takeda: he put camp at Shikata castle and launched a fierce attack with the other armies, but in this battle the spotlight was occupied by his little brother Nobutaka.

1578 was also the year of Araki Murashige's treason: Nobutada, Nobukatsu, Nobukane and Nobutaka joined forces with Nobunaga together with the "Echizen Band" in Settsu to deal with the issue. Nobukatsu encamped in Onobara with his brothers, but they didn't have much chances of action.

The year 1579 started with the continuation with the campaign of Harima: the previous month Nobukatsu was posted at Kema village together with his uncle Nobukane, Takikawa Sakon and Muto Soemon. On the Third Month, together with his brothers and uncle he went to the Capital to meet with Nobunaga and from there they departed for the Itami front.

They moved to Harima on the Fourth month.

This was also the year of the so-called "Iga fiasco".

Apparently Nobukatsu was expected by his father and brothers to keep on fighting on the Itami front, were Nobutada had his hands full, instead, he focused on a punitive expedition against the "notorius lair of bands of evildoers" just to be defeated on the borders of the "small but intractable Province".

On his harsh letter of reprimand Nobunaga tried to explain Nobukatsu's action supposing that instead of making his subjects suffer on an expedition to the metropolitan provinces he decided to neglect his duty by directing them on a campaign in a closer territory: Nobunaga called him "immature" and "gullible" for his lack of far-sight and the troubles that his failed campaign rappresented for the clan.

The letter mentioned also an intention of breaking "the parental tie" between them in case Nobukatsu's "composition really is like this".

Nobunaga's wrath saw no boundaries, but apparently he was more "patient" with his sons. As it's true that after this Nobukatsu didn't perform in any other of his father's campaign, it's also true that in 1580 he received the request (together with Nobutada) to build his residence in Azuchi, and that he took part in all of the next feasts and events held by his father, assuming that he was completely pardoned.

His chance to prove his goodwill finally came in 1581, when, with his father's blessings, he invaded Iga Province again.

This time the strategy was massive and capillar, and none of the Iga "rebels" were spared: Nobukatsu focused on Iga district, Nobukane took care of Yamada and Nabari was the playground of Niwa Nagahide, Tsutsui Junkei and others.

Tsutsui Junkei took care of those confederates who were trying to escape to the mountains, exterminating them with the support of his men.

The front was secured by the end of the month and the report pleased Nobunaga, who confirmed three districts of Iga in fief to Nobukatsu and one to Nobukane.

After Nobunaga and Nobutada's deaths in 1582 and the facts of the Kiyosu Conference, Nobukatsu was granted the provinces of Owari and Ise and Kiyosu castle.

Together with Hideyoshi and Nobutaka he was declared the guardian of the young Sanposhi, Nobutada's first son and heir to Oda clan.

It's around this time that he took back the Oda surname and went by Oda Nobukatsu.

Speaking of the attitude of Nobukatsu, he's usually considered the one with the worst character out of the three Oda brothers.

He gave Hideyoshi lots of troubles after 1582 because of his arrogant and selfish personality, something that penalized him in the long run.

The fact that Nobukatsu had a terrible character, and that Nobutaka's was better, was also reported by missionaries at the time, but it's uncertain to what they referred.

Nobunaga loved him, indeed.

This is explicated in the report of the "Kyoto Cavalcade" in 1581: Nobutada was the main star of the "Branches" ("gorenshi") with an escort of 80 horsemen, but he's closely followed by Nobukatsu and his 30 horsemen.

Nobukane, Nobutaka and Nobusumi sported only 10.

Sure, these numbers reflected the size of their domains, but if Nobukatsu's "wisdom was less than normal" as people likes to state, it's not plausible that Nobunaga favoured him so much compared to Nobutaka.

On this matter, it's also frequently mentioned that Nobukatsu received better treatment because his mother was from a more prestigious family than Nobutaka's: but don't we know that Nobunaga never cared for things like "family prestige" and was a fervent meritocraut..?

I think that Nobunaga had simpathy for Nobukatsu because he recognized his stubborn and volatile personality as "strong traits" of the Oda family. Yet, those were also flaws to fix, since they were index of an "immature" personality, as Nobunaga stated in the letter of 1579.

In an attempt to follow his father suggestion, since he was basically his retainer besides being his son, I like to think that Nobukatsu developed a very sly personality... The one of an impatient man feigning patience.

ODA Nobutaka (1558-1583)

Nobutaka was the third son of Nobunaga and his childhood name was Sanshichi (三七), maybe a reference for being born on the 7th Day of the 3rd Month.

His mother's identity is still questioned, but usually she's recognized as a concubine who was a member of the Saka clan, a powerful family from Ise; he was probably born in what was the residence of Okamoto Munenori (also known as Yoshikatsu), located in the Tsushima area.

Following the destiny of his brother Nobukatsu, he was sent to Ise to be adopted by the Kanbe family in 1569 and made castellan of Kanbe castle, after the victory of Nobunaga in his Ise campaign against the Kitabake clan.

His adoptive father was Kanbe Tomomori. He was married to one of his daughters, Suzuyo (鈴与), shortly after.

It's reported that since Tomomori treated the young Sanshichi coldly, Nobunaga had him confined in Hino castle (also known as Nakano castle) in Omi prefecture and killed all the retainers of Tomomori who protested against his decision-- Which made Nobutaka the head of Kanbe clan in 1571.

In 1572 he had his genpuku together with his brothers Nobutada and Nobukatsu at Gifu castle, where he got the name Kanbe Nobutaka.

His military campaign basically followed that of Nobukatsu, so it's useless to list all the battles again.

As I mentioned above, he made an impression at the siege of Kanki in 1578.

Ota in his Shinchoukoki reports that he "broke his back to be the first at the enemy, competing in nimbleness with the footsoldiers", implying an unknown prowess and military agility.

Another point of interest is that in 1578, when Nobunaga was reported about Araki's betrayal and rushed to Kyoto to follow the negotiations, Nobutaka was left in charge of things at Azuchi together with a few other reatainers, before receiving orders to join his brothers in Settsu province to deal with the issue. This surely means that Nobunaga gave merit to Nobutaka of his responsible character.

Unfortunately the impression is that Nobutaka lacked a good amount of his brothers' charisma: in 1582, after word of Nobunaga's death reached Sakai, he was deserted by his army of 14000 soldiers, meaning that none recognized his authority.

Sure the fact that Nobunaga intervened so blatantly in 1571 to "protect" him didn't legitimate his role in front of his new clansmen, but also the fact that Tomomori was left alive never really gave the idea to their retainers that he was the "real head" of the clan.

It's due noting that the first thing that Nobutaka did in 1582 was reaching for Osaka to kill another of the Branches members, his cousin Nobusumi.

Nobusumi sure had some suspicious ties: he was the first son of Nobuyuki, the younger brother that Nobunaga killed back in 1557 after his betrayal, and he was married to a daughter of Akechi Mitsuhide, the man who just murdered Nobunaga, but there was no actual reason to see Nobusumi as an enemy, given how dearly Nobunaga took care of him.

In my opinion, Nobutaka was already worrying about the succession here, and Nobusumi looked like best candidate as the head of the Oda clan: he could boast support from his father-in-law, blood ties with Nobunaga and even faithful retainers, without considering the great location which was Osaka at the time.

The one who looked like the meeker of the three brothers, now revealed his greed and demanding personality: he could boast the support of the veterans of the Oda clan, but that wasn't enough, and the Kiyosu conference saw him on the losing side.

Hideyoshi granted him the home province of Mino and Gifu castle, but that wasn't enough, and soon after he entered a conflict with Hideyoshi which led to his ultimate defeat.

Famous is his waka, the poem written before one's death:

"You had killed the one you had served,

May gods strike you down, Hashiba Chikuzen".

If I see Nobukatsu as "an impatient man feigning patience", I have the exact opposite impression of Nobutaka: he had to feel frustrated for his situation, the lack of a solid defense behind his back from the Kanbe and the impossibility to get a proper spotlight in battle, seeing how his brothers and Nobunaga's vassals looked way more eager to show off in front of their lord than him, who couldn't do much given the little resources of his tiny domain.

Nobutaka let out all the frustration that he had to swallow as a minor lord. In 1582 he got back the Oda surname and as Oda Nobutaka he let the same fury and impatience displayed at Kanki led his next steps towards legitimacy...

A FEW FINAL WORDS ON THE GORENSHI

As this long, staggering article comes to a conclusion, I feel like spending a few other words about the gorenshi, the "branches" of the Oda family considered the "bone structure" of Nobunaga's army.

I talked about Nobunaga's sons, but it doesn't feel right to leave Nobusumi and Nobukane out of this.

Nobusumi was Nobunaga's nephew, the son of Nobuyuki.

He was born in 1555 and was spared by Nobunaga's fury thanks to the intervention of Dota Gozen, the mother of both Nobunaga and Nobuyuki.

Nobunaga decided to leave the young boy to Shibata Katsuie's care, making him his adopted son. He went by the childhood name of Boumaru (坊丸).

The surname "Tsuda" that Nobusumi adopted after his genpuku derived from another branch of the Oda clan. It was as a way to imply that he was from a different kin of Nobunaga, but still related to him. So in 1564 he was known as Tsuda Nobushige.

His first contact with his uncle is mentioned in 1574, when he attended a tea party in Gifu hosted by Nobunaga. That same year he was one of the lucky retainers who had the chance to witness the imperial treasure of Ranjatai, a perfumed wood preserved in Todaiji that Nobunaga visioned (and kept a bit of as a souvenir) after he was granted permission by the Emperor.

His uijin battle is recorded, and it was against the Echizen Ikko Ikki in 1575, a campaign in which Nobukatsu and Nobukata took part too.

He was assigned holdings in Takashima district after the desertion of Isono Kazumasa in 1578 and this same year he married Akechi's daughter.

In 1582 he was ordered by Nobunaga to support Nobutaka's invasion of Shikoku, so he was stationed at Osaka castle.

Because of his new location, Nobunaga ordered him and Niwa Nagahide to take care of Ieyasu during his trip to Kansai once he reached Osaka-- Another merry chance to prove his worth, that unfortunately didn't happen because of the Incident of Honnoji.

Nobukane was one of Nobunaga's younger brothers.

He was born in 1543 at Owari, and in his childhood he went by the name Sanjuro (三十郎).

Following the destiny of Nobukatsu and Nobutaka, in 1569 he was adopted into the Nagano clan of Ise, gaining Ise-Ueno castle in the process; later Nobunaga cancelled the adoption though, giving Nobukane the Oda surname back.

After the defeat of the Azai Asakura alliance in 1573, he was given custody of his sister Oichi and her three daughters, letting them to stay at Anotsu castle (or Kiyosu, depending on the version) with Nobunaga's blessing.

It's reported that Nobukane was quite affectionate to his nieces as he held in great consideration their father: "It is unbearable to think of the extinction of the Asai family line", he said.

Nobukane was famous for his passion for arts and aestheticism, he was in fact a decent painter and a fan of tea ceremony.

After Nobunaga's death he joined the side of Hideyoshi at the Kiyosu Conference, that granted him a serene life 'til 1590, when he met Hideyoshi's disappointment and shaved his head to live in seclusion at a temple in Kyoto.

Apparently Hideyoshi pardoned him and called him back to his ranks in 1598. He took part to the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 as Ishida's subordinate. Even if he fought in the enemy army, Ieyasu spared his life but relieved him of part of his domain.

He died in mysterious circumstances in 1614 while being in service of Toyotomi Hideyori at Osaka castle, right before the siege of Osaka.

In an attempt to clarify my vision of the story I decided to write and share this series of posts related to Nobunaga's family, expecially his sons, daughters and nephews, since there's so little information about them.

I don't think that all these characters are going to star in my next Nobunaga's manga project, Hana no Ka wa tsugu ("HanaKa" for short), but once I started I couldn't stop and I had to indagate further. Unfortunately I could access only a little bit of material and apparently there are many parts left out in official storiography anyway.

So, keep in mind that the posts going under the "projects" tags do have a historical foundation, but I also took the liberty of adding personal interpretations and speculations according to my narrative needs (but don't worry, I'll make sure to separate the "historical" from the "fictional" information clearly enough)-- Obviously if you know other historical bits that you want to share and could help with broadening the biographies of these characters feel free to comment and share!

Well, after this boring introduction, let's go to the actual contents!

This first post will focus on Nobunaga's sons, or at least the first three of them.

Of course we'll start with Nobunaga's firstborn and heir, Nobutada.

He was born in 1557 in Owari province at the Ikoma mansion, his mother being one of Nobunaga's (favourite) concubine, Kitsuno (吉乃, sometimes also spelled as "Yoshino").

His childhood name was Kimyoumaru (奇妙丸), with "奇妙" meaning "strange", "bizarre"-- It's said that the first time that Nobunaga saw his child's face commented on it saying the he had "a strange face", so he picked such a name for him.

In 1567, following the attempt to form an alliance between the Oda and the Takeda, Nobutada received Matsuhime (松姫), Takeda's daughter, as his wife. The girl kept staying at the Takeda household because of her young age, though, where she'd be treated as "the entrusted lawful wife of Nobutada".

In 1572 he had his genpuku ceremony, where he got the name Oda Kankuro Nobushige (勘九郎信重), that became Nobutada later on.

Right after the genpuku, he had his uijin, his first military campaign, when Nobunaga agreed to bring him to the Kohoku campain against the Azai.

On the same year, Takeda Shingen attacked the Totomi province, causing the reaction of Ieyasu Tokugawa and consequently of his ally, Nobunaga; the marriage between Nobutada and Matsu was broken.

After his first battle, Nobutada kept on fighting almost continuosly, assisting his father: he took part to the campaigns against Honganji (1573), Nagashima (1574) and Nagashino (1575).

In 1575 he led the attack against Iwakura castle, taking it after executing all its inhabitants.

In 1576 he was entrusted Gifu Castle together with the family headship and Owari and Mino provinces.

From there on was another series of battles and showers of titles and honors from the Imperial family and his father, 'til the definitive defeat of Takeda Katsuyori and the extermination of his whole family.

In 1582 when at age 25 he could boast an outstanding career.

It's curious to note that after the "Matsuhime incident" he didn't marry again.

Weird, since back in the time to have a family and grant discendants to the clan was of the uttermost importance.

He did fathered two children, though: Hidenobu, born on 1580 (his mother was a concubine, probably a daughter of Shiokawa Nagamitsu, a certain Suzu [寿々]) and Hidenori, born on 1581 (no informations on his mother are available).

--There's a theory according which Nobutada and Matsuhime kept a letter correspondence and the two never stopped loving each other: proof (?) is that Matsuhime became a nun only after Nobutada's death, and that she went by the nun name 信松尼, using the "松" of her proper name and the 信 from "Nobutada"... But as suggestive as the story is, an actual historical source is not provided (I mean, also her father's name started by "信")...

From this short account on his life you can tell that Nobutada could sport an ambitious and aggressive personality: his direct attacks and calculating cruelty made him the quintessence of a Sengoku warrior, and he also shared the tastes of his father when it came to entertainment.

There are mentions of various precious presents from Nobunaga, and reciprocal tea cerimonies hosted after the built of Azuchi castle (1577/78).

He enjoyed sumo matches with his brother Nobukatsu in Azuchi (1578/80) and his father's calvacades and sagitcho festivals through Kyoto (1581/82); he was a fan of horse riding: in 1581 he ordered men of Owari and Mino to build a riding ground by the the riverbed of Nagarakawa, where he used to ride everyday.

But it wasn't just because of similar hobbies or mere war prowess that Nobunaga favoured Nobutada: he was also assigned managing tasks which perfect execution proved his reliability.

He took care of the work on Azuchi's castle during Nobunaga's trip to Kyoto (1576), he was assigned to found the reconstruction of the Ise shrine (1582) and he managed to reconstruct the destroyed residence of Shingen in Kofu, turning it into a majestic temporary palace where Nobunaga set his quarters (1582).

Keeping this image in mind, it was no surprise that in in 1582 Nobunaga was planning to give the administration of the state affairs to his capable son.

When people think of Nobutada, they like to imagine a perfect fine man, a sort of Nobunaga but with an amiable personality.

In my opinion Nobutada shared the same exact personality of Nobunaga, but probably without any of his rage fits, since we can't find any mention of them, thus probably the image of a "reasonable" person.

By scrolling his deeds I can't help but imagine Nobutada as a son eager to please his father, but also to prove himself better than him: he was aware that being an "equal" to Nobunaga was not enough, so here's his omnipresence on the battlefield, his rushed attacks, his bravery and his cruelty: he never hesitated to cut heads to present to his father, the most precious being those of Katsuyori and his son Nobukatsu (this sure was a popular name back then, uh XD ?) or to exterminate the clans who proved disobedient.

Lamers mentions that Nobunaga wanted to cut the head of Katsuyori himself, so when Nobutada proceeded to do it himself, he was probably uncaring of his father's wish, yet completely devoted to his cause, aware that he was about to inherit his legacy.

ODA Nobukatsu (1558-1630)

Nobukatsu was Nobunaga's second son.

He was born in 1558 at Ikoma mansion, and again his mother is supposed to be Kitsuno, also if this theory is being contested recently, as in Nobutada's case.

His childhood name was Ochasenmaru (茶筅丸).

In 1569 Nobunaga decided to attack the Ise province, where he clashed against the Kitabatake clan, led by Tomonori and his son Tomofusa.

The one against Okawachi castle was a pretty massive siege, that Nobunaga won by reducing his opponents to starvation: Tomonori surrendered and offered the headship of his family together with their home castle to Ochasen as long as their lives were spared. Nobunaga agreed and put a young Nobukatsu into Okawachi castle with Tsuda Kazuyasu as his protector.

He then divided the other vital spots of the province through Takigawa Kazumasu and his younger brother Nobukane, who gained the castle of Ise-Ueno, thus pacificating Ise.

To enforce his position, Ochasen was married to Yukihime (雪姫), a daughter of Kitabatake Tomonori.

In 1572 Ochasen had his genpuku, where he got his name of Kitabatake Tomotoyo. He got the name Nobuoki after he became the head of the Kitabatake clan, in 1575.

In 1576 he proceeded to assassinate his father-in-law, apparently under Nobunaga's orders, thus turning into the absolute governor of the large province of Southern Ise.

Nobukatsu is famous for his "botch" at Iga invasion in 1579, but truth is that his military prowess was no less than Nobutada's, despite the little chances that he had to shine, due to unfavorable position rather than poor skills in battle, in my opinion.

We have no mention of Nobukatsu's uijin, but the first battle that he took part in was the Delta Campaign against Nagashima's Ikko Ikki in 1574. He led one of the large ships the composed the joined operations of the naval units: he was escorted and supported by his troop commanders and was part of that "sight as dazzling as a multitude of shining stars seen among swirling clouds", as reported by Ota in his Shinchoukoki.

In 1575 he took part in the Echizen Campaign, part of that "army of thirty thousand" which units "competed with every other".

We have to wait for 1577 to see Nobukatsu back in action: together with his brothers, the joint armies of Owari, Mino, Omi and Ise assembled in Kii Province to face the Saika's Ikko Ikki. Their "echelon" was sent to follow Mitsuhide's detachment on the main road, which was "full of obstacles".

In 1578 Nobukatsu appeared again on the Osaka front, together with other famed generals, under the lead of Nobutada, which was designed by Nobunaga as the commander-in-chief of the campaign, being the de-facto head of the Oda Clan since 1576.

He took part in a reconnaissance mission in Harima on the same year, followed by the siege of Kanki to face the Takeda: he put camp at Shikata castle and launched a fierce attack with the other armies, but in this battle the spotlight was occupied by his little brother Nobutaka.

1578 was also the year of Araki Murashige's treason: Nobutada, Nobukatsu, Nobukane and Nobutaka joined forces with Nobunaga together with the "Echizen Band" in Settsu to deal with the issue. Nobukatsu encamped in Onobara with his brothers, but they didn't have much chances of action.

The year 1579 started with the continuation with the campaign of Harima: the previous month Nobukatsu was posted at Kema village together with his uncle Nobukane, Takikawa Sakon and Muto Soemon. On the Third Month, together with his brothers and uncle he went to the Capital to meet with Nobunaga and from there they departed for the Itami front.

They moved to Harima on the Fourth month.

This was also the year of the so-called "Iga fiasco".

Apparently Nobukatsu was expected by his father and brothers to keep on fighting on the Itami front, were Nobutada had his hands full, instead, he focused on a punitive expedition against the "notorius lair of bands of evildoers" just to be defeated on the borders of the "small but intractable Province".

On his harsh letter of reprimand Nobunaga tried to explain Nobukatsu's action supposing that instead of making his subjects suffer on an expedition to the metropolitan provinces he decided to neglect his duty by directing them on a campaign in a closer territory: Nobunaga called him "immature" and "gullible" for his lack of far-sight and the troubles that his failed campaign rappresented for the clan.

The letter mentioned also an intention of breaking "the parental tie" between them in case Nobukatsu's "composition really is like this".

Nobunaga's wrath saw no boundaries, but apparently he was more "patient" with his sons. As it's true that after this Nobukatsu didn't perform in any other of his father's campaign, it's also true that in 1580 he received the request (together with Nobutada) to build his residence in Azuchi, and that he took part in all of the next feasts and events held by his father, assuming that he was completely pardoned.

His chance to prove his goodwill finally came in 1581, when, with his father's blessings, he invaded Iga Province again.

This time the strategy was massive and capillar, and none of the Iga "rebels" were spared: Nobukatsu focused on Iga district, Nobukane took care of Yamada and Nabari was the playground of Niwa Nagahide, Tsutsui Junkei and others.

Tsutsui Junkei took care of those confederates who were trying to escape to the mountains, exterminating them with the support of his men.

The front was secured by the end of the month and the report pleased Nobunaga, who confirmed three districts of Iga in fief to Nobukatsu and one to Nobukane.

After Nobunaga and Nobutada's deaths in 1582 and the facts of the Kiyosu Conference, Nobukatsu was granted the provinces of Owari and Ise and Kiyosu castle.

Together with Hideyoshi and Nobutaka he was declared the guardian of the young Sanposhi, Nobutada's first son and heir to Oda clan.

It's around this time that he took back the Oda surname and went by Oda Nobukatsu.

Speaking of the attitude of Nobukatsu, he's usually considered the one with the worst character out of the three Oda brothers.

He gave Hideyoshi lots of troubles after 1582 because of his arrogant and selfish personality, something that penalized him in the long run.

The fact that Nobukatsu had a terrible character, and that Nobutaka's was better, was also reported by missionaries at the time, but it's uncertain to what they referred.

Nobunaga loved him, indeed.

This is explicated in the report of the "Kyoto Cavalcade" in 1581: Nobutada was the main star of the "Branches" ("gorenshi") with an escort of 80 horsemen, but he's closely followed by Nobukatsu and his 30 horsemen.

Nobukane, Nobutaka and Nobusumi sported only 10.

Sure, these numbers reflected the size of their domains, but if Nobukatsu's "wisdom was less than normal" as people likes to state, it's not plausible that Nobunaga favoured him so much compared to Nobutaka.

On this matter, it's also frequently mentioned that Nobukatsu received better treatment because his mother was from a more prestigious family than Nobutaka's: but don't we know that Nobunaga never cared for things like "family prestige" and was a fervent meritocraut..?

I think that Nobunaga had simpathy for Nobukatsu because he recognized his stubborn and volatile personality as "strong traits" of the Oda family. Yet, those were also flaws to fix, since they were index of an "immature" personality, as Nobunaga stated in the letter of 1579.

In an attempt to follow his father suggestion, since he was basically his retainer besides being his son, I like to think that Nobukatsu developed a very sly personality... The one of an impatient man feigning patience.

ODA Nobutaka (1558-1583)

Nobutaka was the third son of Nobunaga and his childhood name was Sanshichi (三七), maybe a reference for being born on the 7th Day of the 3rd Month.

His mother's identity is still questioned, but usually she's recognized as a concubine who was a member of the Saka clan, a powerful family from Ise; he was probably born in what was the residence of Okamoto Munenori (also known as Yoshikatsu), located in the Tsushima area.

Following the destiny of his brother Nobukatsu, he was sent to Ise to be adopted by the Kanbe family in 1569 and made castellan of Kanbe castle, after the victory of Nobunaga in his Ise campaign against the Kitabake clan.

His adoptive father was Kanbe Tomomori. He was married to one of his daughters, Suzuyo (鈴与), shortly after.

It's reported that since Tomomori treated the young Sanshichi coldly, Nobunaga had him confined in Hino castle (also known as Nakano castle) in Omi prefecture and killed all the retainers of Tomomori who protested against his decision-- Which made Nobutaka the head of Kanbe clan in 1571.

In 1572 he had his genpuku together with his brothers Nobutada and Nobukatsu at Gifu castle, where he got the name Kanbe Nobutaka.

His military campaign basically followed that of Nobukatsu, so it's useless to list all the battles again.

As I mentioned above, he made an impression at the siege of Kanki in 1578.

Ota in his Shinchoukoki reports that he "broke his back to be the first at the enemy, competing in nimbleness with the footsoldiers", implying an unknown prowess and military agility.

Another point of interest is that in 1578, when Nobunaga was reported about Araki's betrayal and rushed to Kyoto to follow the negotiations, Nobutaka was left in charge of things at Azuchi together with a few other reatainers, before receiving orders to join his brothers in Settsu province to deal with the issue. This surely means that Nobunaga gave merit to Nobutaka of his responsible character.

Unfortunately the impression is that Nobutaka lacked a good amount of his brothers' charisma: in 1582, after word of Nobunaga's death reached Sakai, he was deserted by his army of 14000 soldiers, meaning that none recognized his authority.

Sure the fact that Nobunaga intervened so blatantly in 1571 to "protect" him didn't legitimate his role in front of his new clansmen, but also the fact that Tomomori was left alive never really gave the idea to their retainers that he was the "real head" of the clan.

It's due noting that the first thing that Nobutaka did in 1582 was reaching for Osaka to kill another of the Branches members, his cousin Nobusumi.

Nobusumi sure had some suspicious ties: he was the first son of Nobuyuki, the younger brother that Nobunaga killed back in 1557 after his betrayal, and he was married to a daughter of Akechi Mitsuhide, the man who just murdered Nobunaga, but there was no actual reason to see Nobusumi as an enemy, given how dearly Nobunaga took care of him.

In my opinion, Nobutaka was already worrying about the succession here, and Nobusumi looked like best candidate as the head of the Oda clan: he could boast support from his father-in-law, blood ties with Nobunaga and even faithful retainers, without considering the great location which was Osaka at the time.

The one who looked like the meeker of the three brothers, now revealed his greed and demanding personality: he could boast the support of the veterans of the Oda clan, but that wasn't enough, and the Kiyosu conference saw him on the losing side.

Hideyoshi granted him the home province of Mino and Gifu castle, but that wasn't enough, and soon after he entered a conflict with Hideyoshi which led to his ultimate defeat.

Famous is his waka, the poem written before one's death:

"You had killed the one you had served,

May gods strike you down, Hashiba Chikuzen".

If I see Nobukatsu as "an impatient man feigning patience", I have the exact opposite impression of Nobutaka: he had to feel frustrated for his situation, the lack of a solid defense behind his back from the Kanbe and the impossibility to get a proper spotlight in battle, seeing how his brothers and Nobunaga's vassals looked way more eager to show off in front of their lord than him, who couldn't do much given the little resources of his tiny domain.

Nobutaka let out all the frustration that he had to swallow as a minor lord. In 1582 he got back the Oda surname and as Oda Nobutaka he let the same fury and impatience displayed at Kanki led his next steps towards legitimacy...

A FEW FINAL WORDS ON THE GORENSHI

As this long, staggering article comes to a conclusion, I feel like spending a few other words about the gorenshi, the "branches" of the Oda family considered the "bone structure" of Nobunaga's army.

I talked about Nobunaga's sons, but it doesn't feel right to leave Nobusumi and Nobukane out of this.

Nobusumi was Nobunaga's nephew, the son of Nobuyuki.

He was born in 1555 and was spared by Nobunaga's fury thanks to the intervention of Dota Gozen, the mother of both Nobunaga and Nobuyuki.

Nobunaga decided to leave the young boy to Shibata Katsuie's care, making him his adopted son. He went by the childhood name of Boumaru (坊丸).

The surname "Tsuda" that Nobusumi adopted after his genpuku derived from another branch of the Oda clan. It was as a way to imply that he was from a different kin of Nobunaga, but still related to him. So in 1564 he was known as Tsuda Nobushige.

His first contact with his uncle is mentioned in 1574, when he attended a tea party in Gifu hosted by Nobunaga. That same year he was one of the lucky retainers who had the chance to witness the imperial treasure of Ranjatai, a perfumed wood preserved in Todaiji that Nobunaga visioned (and kept a bit of as a souvenir) after he was granted permission by the Emperor.

His uijin battle is recorded, and it was against the Echizen Ikko Ikki in 1575, a campaign in which Nobukatsu and Nobukata took part too.

He was assigned holdings in Takashima district after the desertion of Isono Kazumasa in 1578 and this same year he married Akechi's daughter.

In 1582 he was ordered by Nobunaga to support Nobutaka's invasion of Shikoku, so he was stationed at Osaka castle.

Because of his new location, Nobunaga ordered him and Niwa Nagahide to take care of Ieyasu during his trip to Kansai once he reached Osaka-- Another merry chance to prove his worth, that unfortunately didn't happen because of the Incident of Honnoji.

Nobukane was one of Nobunaga's younger brothers.

He was born in 1543 at Owari, and in his childhood he went by the name Sanjuro (三十郎).

Following the destiny of Nobukatsu and Nobutaka, in 1569 he was adopted into the Nagano clan of Ise, gaining Ise-Ueno castle in the process; later Nobunaga cancelled the adoption though, giving Nobukane the Oda surname back.

After the defeat of the Azai Asakura alliance in 1573, he was given custody of his sister Oichi and her three daughters, letting them to stay at Anotsu castle (or Kiyosu, depending on the version) with Nobunaga's blessing.

It's reported that Nobukane was quite affectionate to his nieces as he held in great consideration their father: "It is unbearable to think of the extinction of the Asai family line", he said.

Nobukane was famous for his passion for arts and aestheticism, he was in fact a decent painter and a fan of tea ceremony.

After Nobunaga's death he joined the side of Hideyoshi at the Kiyosu Conference, that granted him a serene life 'til 1590, when he met Hideyoshi's disappointment and shaved his head to live in seclusion at a temple in Kyoto.

Apparently Hideyoshi pardoned him and called him back to his ranks in 1598. He took part to the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 as Ishida's subordinate. Even if he fought in the enemy army, Ieyasu spared his life but relieved him of part of his domain.

He died in mysterious circumstances in 1614 while being in service of Toyotomi Hideyori at Osaka castle, right before the siege of Osaka.

Friday, 11 April 2014

Nobunaga the Tourist

What's the point of unifying the country is you can't walk around it freely and visit its wonderful spots to enrich your soul?

It's probably a question that rose in Nobunaga's mind after he befriended the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki in 1568 and entered in touch with the Imperial court and the merchants of Sakai and Osaka.

Nobunaga remained a warrior through the most of his life, and if in the Chronicles of Lord Nobunaga there are many reports about various field trips and excursions, those were mostly for military purposes, studies of the terrain frequently sprinkled by energic hunt sessions or horseback rides.

We had a first attempt at what looked like a "touristic deed" in 1572, during the fortification of Mount Toragoze, part of the preparations that led to the siege of Odani castle and the fall of the Azai and the Asakura.

As the massive job came to a conclusion, Nobunaga and his generals stopped to savour the view of the mountains, and even if their pride was still directed to the wonderful engineering work, the passage of the Chronicles showed an unusual lyrical tone:

"It was difficult to find words to describe the beautiful scenery stretching before one's eye in every direction, or to describe how well Nobunaga had constructed his sturdy castle."

The Chronicles of Lord Nobunaga, Ota Gyuuchi - as translated by JSA Elisonas, JP Lamers, p.174

Ota took also his time to pinpoint the various places of interestes that one could enjoy from the top of the mountain: the lake Biwa, the mountaintops of Hiei and Hachiouji, and the Ishiyama temple, one of the Thirty-three Pilgrimage Sites of the Western Provinces.

It's worth noting that this same spot is now part of a touristic hiking track where visitors can imagine the flavour of the siege. You can find informations on this website.

Another interesting bit of tourism happened in 1575, after Nobunaga managed to seize the provinces of Kaga and Echizen.

It's mentioned that on the 12th day of the 10th month, on the way to Kyoto, he took his time to inspect some works of reconstruction on the Seta bridge that started a few months earlier, "for the sake of the realm and out of compassion for the travellers coming and going" (p.232).

Ota reported his impressions: "The bridge was indeed something stupendous, and all were amazed" (p.241).

Ota reported his impressions: "The bridge was indeed something stupendous, and all were amazed" (p.241).

Nobunaga visited again this important spot, part of the Eight Views of Omi: in 1579, when he lodged in a nearby teahouse.

On the same period, during his stay in Kyoto he profitted to visit the beautiful complex of Kiyomizudera.